When History Is Framed as ‘White People Bad,’ Everyone Loses

Make It Make Sense: A Series on Media, Messaging, and the Manipulations We Miss

(This is the first article in the series, digging into how cultural institutions and media framing can distort history and deepen division.)

On Thursday, August 14, 2025, fitness icon and television personality Jillian Michaels appeared on CNN’s NewsNight with Abby Phillip to discuss President Donald Trump’s recent directive ordering the Smithsonian Institution to review its exhibits.

The Trump administration’s letter, sent August 12 to Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III, stated the review was intended to “celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives, and restore confidence in our shared cultural institutions.”

That framing stands in sharp contrast to CNN’s coverage, which immediately raised concerns about censorship, erasure, and attempts to “rewrite” history.

Michaels found herself in the middle of a heated CNN panel, accused of defending “whitewashing” when in reality she was challenging the Smithsonian’s drift into politicized storytelling—where complex events are boiled down into a single narrative: white people as oppressors, everyone else as victims.

The exchange was tense, but beneath the cross-talk lies a deeper question: how should we frame American history—and what happens when we reduce it to a single storyline?

“He’s not whitewashing slavery,” Michaels said. “And you cannot tie imperialism and racism and slavery to just one race, which is pretty much what every single exhibit does.”

Her comments sparked outrage. Critics blasted CNN for even allowing her on air, claiming she was unqualified to weigh in on historical accuracy. Others attacked her directly on social media, with outlets like HuffPost running headlines accusing her of having a “meltdown defending white people.”

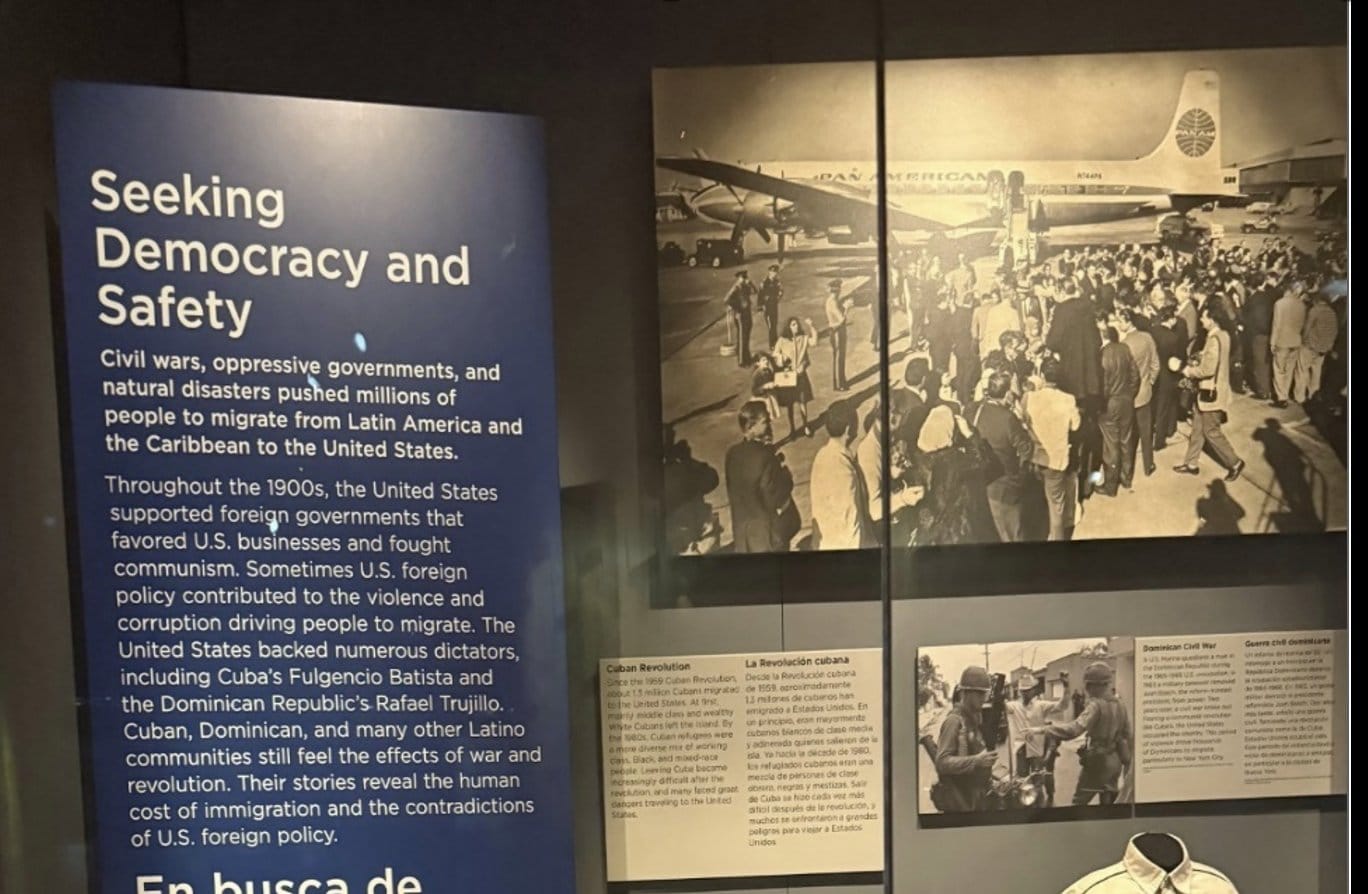

The Cuba Example

On X, Michaels gave a concrete example. She posted the photo above of a Smithsonian exhibit about Cuban migration that suggested Cubans fled because of U.S. foreign policy. What it left out was pivotal: that mass migration accelerated after Fidel Castro’s communist revolution, when political opponents were jailed, businesses seized, and dissidents executed.

As Michaels put it:

“Like the rest of the exhibit, this framing reduces a complex history to a narrative in which the United States alone destabilized the developing world. I oppose interventionist U.S. foreign policy, but this is not an honest or complete portrayal of what happened in Cuba. Period.”

By omitting Castro’s brutality, the exhibit didn’t just leave out context—it conditioned visitors to see America as the permanent aggressor.

The “Whiteness” Exhibit

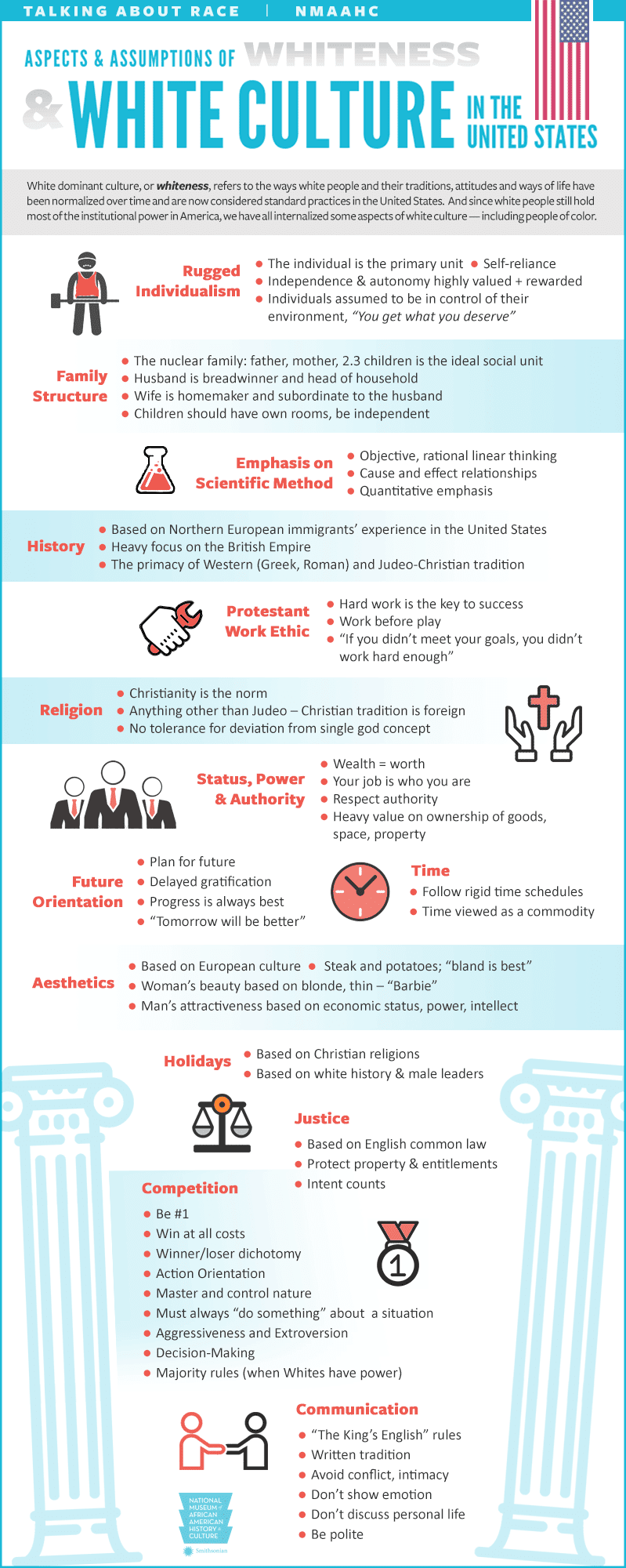

And this isn’t the first time the Smithsonian has faced backlash for this kind of framing. In 2020, the National Museum of African American History and Culture published a chart titled “Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness and White Culture in the United States.”

The chart claimed that traits such as individualism, hard work, punctuality, the nuclear family, and even “objective, rational linear thinking” were products of “white-dominant culture.” Critics across the spectrum blasted the display for suggesting that these values were inherently racial rather than universal.

Once again, like the Cuba exhibit, the ‘Whiteness’ chart boiled down a complicated reality into a single, divisive story—America as the villain, whiteness as inherently toxic. Instead of celebrating shared values that cut across race and culture, the exhibit framed them as evidence of racial dominance. It turned principles most Americans recognize as positive into signs of cultural toxicity.

Why It Matters

Whether you agree with Michaels or not, her critique exposes how selective framing doesn’t just shape history—it distorts public understanding of the present.

When young people see museums framing history this way, it doesn’t just teach them facts—it shapes how they see themselves and their country. That kind of identity-shaping is powerful, which is why accuracy and balance matter so much.

Both sides raise valid concerns: history should be neither sanitized to protect feelings nor twisted into an ideological weapon against an entire race.

And this is where the hard questions come in: Why are so many Americans comfortable with exhibits and narratives that paint “white people” broadly as the villains of history? Nothing good comes from teaching children that one race is inherently oppressive while another is inherently victimized. Isn’t this the same kind of reductionist thinking we’ve spent decades trying to move beyond?

We can—and must—acknowledge the horrors of slavery, Jim Crow, and systemic racism. But history is richer than a single storyline. When we frame everything as “white people bad,” we shut down honest conversation, fuel division, and rob younger generations of the nuance they need to understand the past and build a better future.

History isn’t a weapon to be used against each other. It’s a mirror—meant to show us the truth in full, even when it’s uncomfortable. And when institutions present that truth selectively, everyone loses.

It’s undeniable that white Americans built and benefited from systems of oppression. But it’s also undeniable that white Americans fought and died to end slavery. It’s undeniable that America has made grave mistakes abroad. But it’s also undeniable that America has been a refuge for millions fleeing tyranny. Both can be true. Both are true.

Reducing history to one side of that ledger may score political points in the present, but it robs future generations of the fuller picture. And it risks hardening racial resentment at a time when unity is already fragile.

So, Make It Make Sense

How does painting all white people as oppressors and all people of color as victims heal our country? What message does it send to a young Black child to be told America is only a story of oppression—or to a young white child to be told their culture is inherently toxic?

It doesn’t. It divides.

Jillian Michaels wasn’t wrong to ask for a fuller picture. History deserves honesty, not oversimplification. Our children deserve complexity, not propaganda. And America deserves institutions that tell our story in full—not through the narrow lens of guilt or grievance, but through the messy, complicated, human truth.

Because when history is framed as “white people bad,” everyone loses.

The question now is: will our institutions rise to the challenge—or will they keep reducing history to a story where some are permanent villains, and others permanent victims?

Comments ()